Blasts from the Past

1971 Honda Z600: Archaic Ancestor of Today’s Civilized Civic

If our initial post seems heavy with Hondas, it’s because we consciously chose to begin with a theme. We know there are plenty of other high-efficiency automobiles out there, and in future posts we plan to cover as many of them as we can.

The Z600 was a tough little car, from a determined man inclined to face adversity with innovation. More importantly, it was the first Honda to catch the attention of U.S. car buyers. Too bad Detroit didn’t notice. . . .

Soichiro Honda began working in a Tokyo garage as a teenager, and repaired fire-damaged cars after Japan’s 1923 earthquake. He built his first successful race car in 1925, at the age of 19. By the 1930s he had his own factory in Komyo, producing piston rings for the Japanese war machine. The factory was bombed to rubble in 1945, but little more than a year later Honda was back in business in Hamamatsu, mating military-surplus Mikuni portable generator engines to bicycles. When Honda ran out of surplus engines, he designed and built his own. Gasoline was scarce, so he tuned it to run on fuel made from pine resin. By 1959, Honda was assembling one million motorcycles annually—making him the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world. Honda bikes were exported to the U.S., and were winning major international races. Racing bikes led to racing cars, which scored a Formula 1 victory in Mexico in 1965, and a dozen Formula 2 wins in 1966.

Meanwhile, Honda’s first civilian four-wheelers had debuted at the Tokyo auto show of 1962: an MG Midget-sized roadster, and a light delivery truck that shared much of the same mechanical platform. Surprisingly sophisticated, the little sports car featured a twin-cam four with multiple carburetors, water cooling, and dual chain drives enclosed in the trailing arms of its independent rear suspension.

By the mid-60s the roadster had spawned a line of larger-engined variants, but Honda shifted his attention again, this time to economical sedans. Again, the influence was clearly British: In size, proportion, and mechanical layout the 1967 N360 resembled an even more austere Mini, if such a thing can be imagined. The bigger-engined (598cc) N600 provided some extra oomph for the export market.

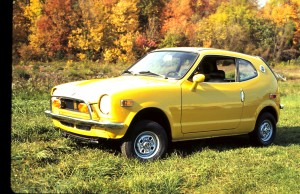

Which brings usto our featured vehicle, the Z600 of 1971-72, which Over Here was more often simply called the Honda Coupe. Smoother and rounder than the sedan, it’s not quite sporty but it’s definitely cute. It’s also clearly the earliest visual ancestor of the first-generation Civic. Most importantly, while it shared the N600 sedan’s mechanical platform, it re-packaged the sedan’s interior space; rather than barely adequate room for four adults, the Coupe provided ample space for two adults and two little Astro Boy fans in the back. Car and Driver (April 1972) even claimed the Coupe’s raked-back windshield and two-inch lower profile were good for another 3 mph at the top end. Wider tires and a neat overhead console (with swiveling map light) helped justify the Coupe’s $135 premium over the sedan.

were good for another 3 mph at the top end. Wider tires and a neat overhead console (with swiveling map light) helped justify the Coupe’s $135 premium over the sedan.

This particular Z600 served its original owner for over 100,000 miles before it was traded in at Keenan Honda in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, where we drove and photographed it about ten years ago. [Please see update to this information in the comments below.]

Despite its proto-Civic looks, the Z600 lacks the refinement that made later Hondas so appealing. For one thing, the doors close with a hollow, tinny clang that’s still infinitely preferable to the brain-warping whine of the door-ajar buzzer.

The front bucket seats are acceptably comfortable, if a bit flat and upright. The gauge layout, which centers a small fuel gauge between a larger speedometer and tachometer, actually comes across as sporty, if in a fussy, 1970s-sort of way, with heavy-handed plastic rims around each dial. In contrast, the classically designed three-spoke steering wheel would look at home in any era. And the overhead console with its ball-swivel map light is just the kind of surprisingly up-market appointment that has always delighted Honda initiates, and helped affirm the loyalty of the Honda faithful. Overall space in the driver’s compartment is just about adequate for the my five-foot, nine-inch and admittedly well-padded frame. The child-size rear seat folds, converting into useable luggage space, which can be loaded through the doors or though the opening backlight–which, with its rounded corners and heavy rim of black rubber, oddly resembles the door on an industrial washing machine. Pulling out the center of the rear bumper accesses the spare tire, so no luggage needs to be unpacked while changing a roadside flat.

The front bucket seats are acceptably comfortable, if a bit flat and upright. The gauge layout, which centers a small fuel gauge between a larger speedometer and tachometer, actually comes across as sporty, if in a fussy, 1970s-sort of way, with heavy-handed plastic rims around each dial. In contrast, the classically designed three-spoke steering wheel would look at home in any era. And the overhead console with its ball-swivel map light is just the kind of surprisingly up-market appointment that has always delighted Honda initiates, and helped affirm the loyalty of the Honda faithful. Overall space in the driver’s compartment is just about adequate for the my five-foot, nine-inch and admittedly well-padded frame. The child-size rear seat folds, converting into useable luggage space, which can be loaded through the doors or though the opening backlight–which, with its rounded corners and heavy rim of black rubber, oddly resembles the door on an industrial washing machine. Pulling out the center of the rear bumper accesses the spare tire, so no luggage needs to be unpacked while changing a roadside flat.

Before we go any  further—in fact, before we start the engine and go anywhere at all—it’s worth remembering that the Honda 600’s chief competitor would have been the noisy, slow, air-cooled VW Beetle, which had only recently crested its U.S. sales peak in 1968. Relatively speaking, however, the Bug did offer 1600 cc, divided up amid four horizontally opposed cylinders discreetly tucked behind the rear wheels. In comparison, the Honda’s 600cc vertical twin not only comes up short by two cylinders and a full liter of displacement, but shakes its shameless shimmy just inches ahead of your toes. Add more revs and the shimmy turns to a tooth-gnashing thump-and-grind.

further—in fact, before we start the engine and go anywhere at all—it’s worth remembering that the Honda 600’s chief competitor would have been the noisy, slow, air-cooled VW Beetle, which had only recently crested its U.S. sales peak in 1968. Relatively speaking, however, the Bug did offer 1600 cc, divided up amid four horizontally opposed cylinders discreetly tucked behind the rear wheels. In comparison, the Honda’s 600cc vertical twin not only comes up short by two cylinders and a full liter of displacement, but shakes its shameless shimmy just inches ahead of your toes. Add more revs and the shimmy turns to a tooth-gnashing thump-and-grind.

And despite the 600’s modest output, the heavily-sprung clutch requires a mighty stomp to the floor, where it feels like it’s sinking into a puddle of muck. The dash-mounted four-speed gearshift pulls in and out and swivels, and generally resembles a Citroën 2CV’s in every manner except for general competence. To engage Reverse, simply twist the gear knob smartly into your right kneecap. And don’t forget that the little Honda’s gears are not synchronized.

And for all its busy soundtrack, the thumping twin displays little enthusiasm for its work. A reasonable cruising speed of 50 mph requires 3800 rpm, where the throttle is completely numb; drop it from fourth down to third and it will wind to 5500 before hitting a fuel-starvation wall. Keep at it, and it will creep up past its 6000 rpm red line. But then what’s the point?

Likewise, the 600’s steering seems sloppy by modern standards, but then improves considerably when you recall a Beetle or a U.S. barge of the same era. It’s the Honda’s ride that truly surprises: softer than we expected, more supple than bouncy, if touched by a constant tingle from the engine. Cornering limits are all we could ask for on 10-inch Pirelli P3’s.

So the Z600 was a bit unsophisticated. . . . Okay, it was downright crude. But it was the kind of crude that puts a smile on your face. The fact that just two years later the same  outfit was turning out infinitely improved, four-cylinder, water-cooled Civics should have run up a red flag in Detroit. But clearly it didn’t, and that explains a lot about how we got to where we are today.

outfit was turning out infinitely improved, four-cylinder, water-cooled Civics should have run up a red flag in Detroit. But clearly it didn’t, and that explains a lot about how we got to where we are today.

2 Responses to Carbon Dating